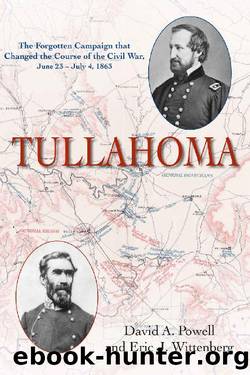

Tullahoma by David A. Powell & Eric J. Wittenberg

Author:David A. Powell & Eric J. Wittenberg [Powell, David A.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: History / United States / Civil War Period(1850-1877)

Publisher: Savas Beatie

Published: 2020-08-25T05:00:00+00:00

Even for those Federals lucky enough not to be detailed to help with the near-Sisyphean task of hauling cannon, limbers, and army wagons up Gilleyâs Hill, two daysâ military limbo proved uncomfortable. Food was short. The men had been issued three daysâ rations to cook and carry with them on June 23. Even under normal circumstances, those supplies would be exhausted by the 26th; the pervasive rain, however, made matters worse. As William Curry of the 1st Ohio Cavalry observed, âduring all this time our blankets were never dried out, and our rations in our old greasy haversacks were a conglomerated mass of coffee, sugar, salt, sow-belly, and hard-tack.â The only available replacements for these ruined rations were in those same wagons back down in Torbertâs Hollowânow seemingly a long way away.24

Reined in by Crittenden and Rosecrans, and with limited prospects for action, Turchinâs cavalry hovered near Lumleyâs Stand on June 25 and 26. Colonel Long dispatched ânine companies of my command to assist in bringing forward the wagons,â and on the afternoon of June 27, Turchin shifted Longâs brigade to Pocahontas, presumably (though this was not specified in the reports) to cover Crittendenâs right flank when he resumed his march toward Manchester. Here, a dry wit at brigade headquarters recorded the most interesting event of the day. âSomeone stole General Turchinâs coffee pot,â he wrote. âIt was of enough importance to send a staff officer in search of it, but he did not find it.â As for the weather, âRained.â25

Turchinâs and then Palmerâs reduced trains finally cleared Gilleyâs Hill by 11:00 a.m. on June 27, after a grueling, nearly nonstop 48-hour effort. But Woodâs division still had to climb the hill. Fortunately, Wood was better prepared and had the advantage of having observed Palmerâs laborious efforts. His trains already had been stripped to the absolute minimum needed for field operations on June 23, and his men set to work with a will. The scene must have been nearly indescribableâthe countryside littered with broken wagons, dead mules, and sputtering pyres of discarded equipment, all mired in a sea of sticky mud and washed by constant, steady, annoying rain. In his memoir, General Stanley described how these conditions rendered the roads nearly impassable. âFoot soldiers marching over the pale clay deployed like slow moving skirmishers,â he recorded; âhorsemen sought their own course; and as for artillery and supply wagons, they sunk in the mud to the axles and stayed there.â26

Despite these obstacles, âat 2 p.m. on the 27th,â Wood reported with evident pride, âthe ascent . . . commenced, and by 1:00 a.m. on the 28th the whole . . . was at the summit. Exactly eleven hours were occupied in the ascent.â Wood credited Brig. Gen. George D. Wagner for his direct supervision of this work, which âwas rapidly, energetically, and skillfully done.â Crittenden thought that for his foresight in stripping his divisional baggage before the march began, Wood was âentitled to the commendation of the general commanding.â27

Meanwhile, as Crittenden struggled, Rosecrans set most of the rest of the army into motion.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber & David Wengrow(1707)

The Bomber Mafia by Malcolm Gladwell(1622)

Facing the Mountain by Daniel James Brown(1553)

Submerged Prehistory by Benjamin Jonathan; & Clive Bonsall & Catriona Pickard & Anders Fischer(1455)

Wandering in Strange Lands by Morgan Jerkins(1430)

Tip Top by Bill James(1416)

Driving While Brown: Sheriff Joe Arpaio Versus the Latino Resistance by Terry Greene Sterling & Jude Joffe-Block(1376)

Red Roulette : An Insider's Story of Wealth, Power, Corruption, and Vengeance in Today's China (9781982156176) by Shum Desmond(1359)

Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History by Kurt Andersen(1353)

The Way of Fire and Ice: The Living Tradition of Norse Paganism by Ryan Smith(1336)

American Kompromat by Craig Unger(1315)

F*cking History by The Captain(1304)

It Was All a Lie by Stuart Stevens;(1300)

American Dreams by Unknown(1286)

Treasure Islands: Tax Havens and the Men who Stole the World by Nicholas Shaxson(1273)

Evil Geniuses by Kurt Andersen(1257)

White House Inc. by Dan Alexander(1212)

The First Conspiracy by Brad Meltzer & Josh Mensch(1174)

The Fifteen Biggest Lies about the Economy: And Everything Else the Right Doesn't Want You to Know about Taxes, Jobs, and Corporate America by Joshua Holland(1126)